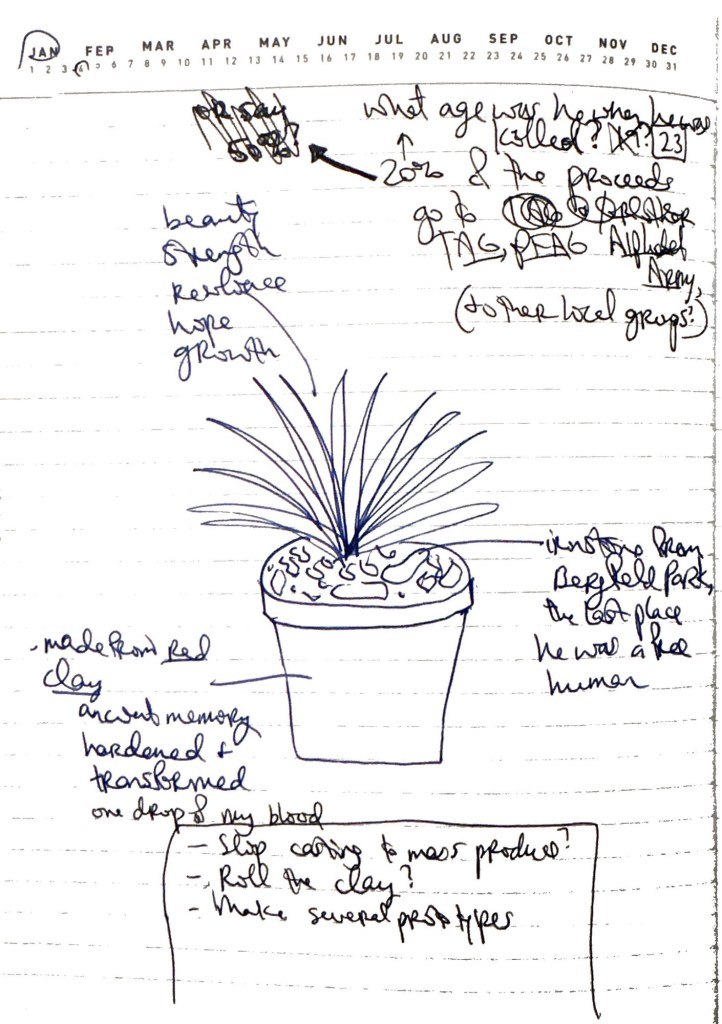

One Saturday in early January, in the middle of cleaning and entertaining my kids, I got an idea for an art project and sketched the notes below.

I’ve been really interested in the life and death of Nicholas West for a little over a year now and continue to feel a strong connection to his story.

The basic idea is…

- A collection of pots thrown from red clay harvested in and around Noonday, TX where Nicholas was tortured and killed

- The pots are different sizes with different biographical information about Nicholas like his birth and death years, text from obituaries, anything significant from his story

- Each pot would have a drop or two of my own blood. I want to make people a little uncomfortable when they pick up the pot and read the description. I want to make his death more tangible and remind people that all soil has seen bloodshed of one kind or another. (On a more cosmic level, I also love the connection between the iron in our blood and the iron in the soil which was all stardust flung across the universe from dying supernovae.) I’ve noticed that men are pretty squeamish about the idea of the blood, and women I’ve told are much more supportive which makes me want to do it even more.

- In the pot will be planted a Yucca filamentosa, native to the southeastern US (from Tyler to Richmond), very hardy, tropical, and structural. The yucca will grow to fit the size of the container that it is in, the yucca is resilient, and in the spring it has a bloom several feet above most other plants.

- Yucca is also the first plant that I really noticed and developed a connection to. It is the first plant I remember finding and foraging and I’ve planted and potted at least five in the last two houses where we’ve lived. I was in a dark place in my life and my interest in plants, yucca specifically, was an encouragement that has continued to center me and excite me while also driving me a little crazy with more ideas than I’ll ever have time for.

- While I still love the idea of Yucca, more recently I’ve considered Hesperaloe parviflora, also known as “red yucca” or “false yucca.” I noticed it in Texas at some point and planted it in my garden 3-4 years ago. I had a naturalist walk around with me and he commented that he liked seeing it growing in Richmond because he didn’t know that it could. I love the idea of a Texas transplant thriving in Richmond and the idea of it being a “false” yucca feels appropriate for the Southern culture of repression and how much of myself I held back from others for so long. Of course I love the red bloom, the color of blood and nectar for hummingbirds stopping for a moment on their impossible migration.

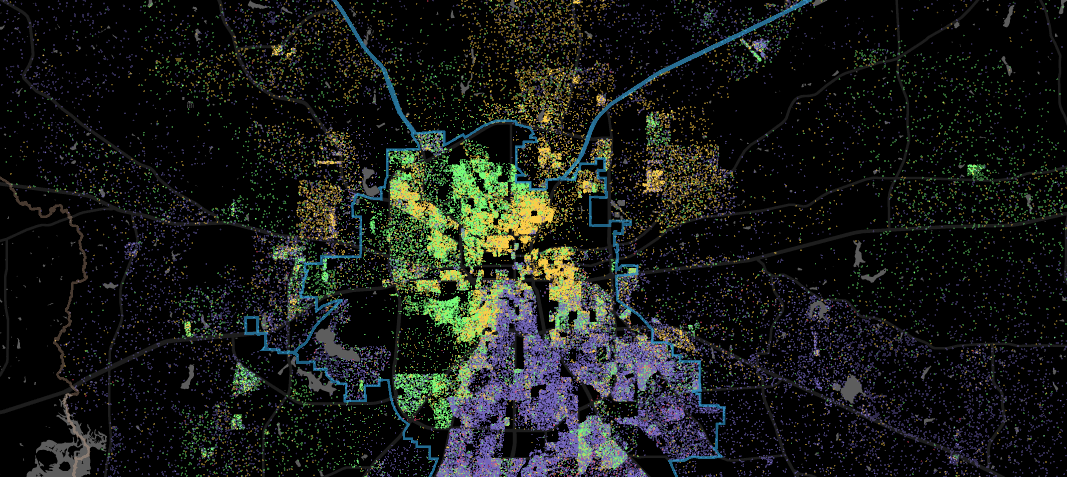

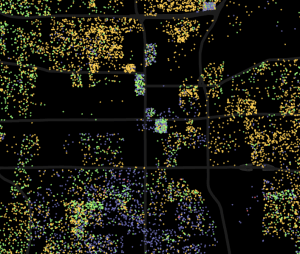

- On the surface of the dirt in the pot I want to scatter bits of ironstone found at Bergfeld Park, the place where Nicholas was picked up, the last place he was free. On my most recent visit to Tyler I pocketed some pieces of the stone and brought them back to a potted yucca I have by our back porch. It has been special to me to have them there as a connection to home

- I’d love to sell replicas of the different styles of pots and give a portion of the proceeds to local LGBT community organizations in the Tyler area.

It would take months or years to really do this as well as I would want to – I haven’t even fired a clay pot since high school. I’d need time to harvest the clay, prototype different styles, and learn how to make them consistently well, etc. So with all that considered in addition to the constraints of full-time employment/parenting life, I’ve accepted that I’m probably not going to attempt it, as much as I want to. It felt better to share the idea here and let it go rather than hold it too tightly.

4.22.25 – Since writing this post I’ve thought more about the possibility of partnering with an artist to make the pots that I could use to plant and we could market the project together. Even still I don’t think I have the time to do it well, but the partnership would be really rewarding and it’s much more realistic to lean on someone’s existing expertise rather than try and develop it myself. It also got me thinking outside the box even more. Maybe this idea should actually be an assignment for a class where everyone chooses an event that deserves more recognition and designs an installation to share the story. Maybe it should just be an online project that collects memories and details from his story. Or maybe this just needs to be a section of my own garden: a shrine to his life and a broader connection to my own story, my hometown, and the resilience, growth, and occasional moments of flourish.

4.24.25 – While reading about “The Burying Grounds Memorial” at the University of Richmond I learned that Yucca, “is often found in the cemeteries of enslaved people, serving as living grave markers.” I have only just gone a few steps down this rabbit hole, but I’ve already found some interesting articles and anecdotes that support using it for the project. It seems the plant has long served to mark the memory of people who might have otherwise been forgotten, to bind their restless spirits after life, and to provide permanent protection to their physical remains.

- “Fieldstones. Yucca plants. Seashells. The last object a loved one touched. For centuries, these items, cultivated from lives and landscapes, marked many graves at burial places for Black people in America.” National Grographic

- “Some of the plots were marked with pieces of quartz or with yucca plants, which were used by many Southern Black families who could not afford stones.” ProPublica

- “The phrase “pushing up yucca” has been coined to describe these graveyards, and there was a Gullah belief that spiny plants restricted the movement of the spirits of the dead.” Society of Ethnobiology

- “Spiky clumps of yucca dot Odd Fellows cemetery as further reminders that this patch of woods was once a curated (if not manicured) space. Though widely found in cemeteries across the country, in African-American tradition specifically, yucca binds restless spirits to their graves. Easily transplanted and nearly ever-lasting, yucca was sometimes planted near the head of a grave in lieu of an expensive stone marker.” Black Wide-Awake

- “Yucca is another plant that marks many early graves even today. It can live hundreds of years and represents eternity. In many African American communities it was also traditionally thought that yucca kept restless spirits in the grave.” City of Birmingham

- “Due to their association with cemeteries, the yucca plant has also taken on an association with the supernatural, as a way to ward off evil spirits.” Lumpkin County Historical Society