A little over three years ago, in the early days of fall, I noticed myself looking forward to the first frost. It had been a season of upheaval in my life and I was tired. Everything in the garden felt like too much: the tomato plants were enormous, mosquitoes continued to test my sanity, and even trees seemed tired from the growth.

I was excited for the cold-weather months. It can be a relief when everything outside looks like death and the work (for a time) is done. I looked forward to hikes and runs when you can see straight through the faded underbrush. What I did not know at that time, when the sunlight cuts across the landscape and flies and dust dance in the cool, dry air of harvest, is that in a couple of months I would lose one of my closest friends forever.

Unable to control the weather, I started to cut back in my own ways. I aggressively unsubscribed myself from email lists. My inbox had become overrun just like everything else. I also decided to stop drinking coffee. I noticed it was making me more anxious than focused, my mind a glutton for information, too busy with ideas and making connections to focus on tasks at work. With less caffeine I found myself breathing more deeply, crying more easily.

As time wound into winter, the landscape began to feel more manageable and muted. There were few weeds to pull, nothing to prune or harvest. During winter we find comfort knowing that nature is just resting, that everything is gone for a time, that there will be flowers and fruit again.

On the night of Christmas Eve, just past the darkest night of the year, I got a text from a friend asking me to call. I immediately felt that someone had died. When I finally reached her, she told me something unimaginable. After I got off the phone, I called another of my closest friends and shared what I couldn’t even fully believe myself.

Then all of the sudden, in my grief and loss, I wanted every bit of the chaos to come back. I wanted to get caught up in the weeds, the insects, the relentless advance of kudzu. The land, now bare and clear, felt more acute, more permanent, more extreme, life cleared out and put away. I wanted the change of seasons that felt familiar, the loss that turns back into life.

At the same time, I was grateful that I had been listening to my sadness over the previous months. I felt like my emotions were very accessible to me in the early days of grief and acceptance. Many times I wondered if leaving religion had also prepared me to grieve.

Sometimes I feel like religions treat death like it’s perennial or cyclical rather than permanent. They believe (and maybe I still believe on some level) that the person has been reborn instead of accepting that they are gone forever. This is just my personal experience, but it has always felt too soon, like a silver lining, to say that someone is in a better place before someone else has let them go.

I want to tie this up with some kind of “and yet” sentence where I channel my inner Margaret Renkl and talk about being grateful for the things that are going well, but it feels more appropriate to just accept and metabolize the loss.

Nature is full of metaphors of rebirth and renewal, but sometimes things do just die. Sometimes species go extinct. Climate change is looking very one-directional these days. So when spring came, and warmer temperatures brought ephemerals, buds, and other signs of life, he was still gone.

Summer followed and my friend was not here to enjoy the cool river on a hot, humid day, or whatever beach trip he had been planning with his family. Fall came around before too long and he wasn’t trick-or-treating or getting cozy on a couch. Then winter again and we all relived in our own way the experience of losing him that cold night. That is cyclical, I suppose. I am always grateful for the chance to remember him, see mutual friends, and let him go all over again.

I recently visited the Negro Burial Ground just east of downtown Richmond in Shockoe Valley. My approach to this site was across a VCU parking lot and through a tunnel under Broad St. As you walk through the tunnel, you emerge onto a huge empty field of beautiful grass that was once yet another parking lot in downtown Richmond. In recent years, the asphalt was removed and this area was designated “A Place of Contemplation and Reflection.” I appreciate this area mostly because it’s a complicated place. There aren’t physical buildings that most people would consider “historic,” but what happened on this one piece of ground (the public execution and careless burial of enslaved and free people) is considered enough to make the place significant today. Once a place of fear and violence, it has been restored to the people of Richmond as a place of silence and careful thought.

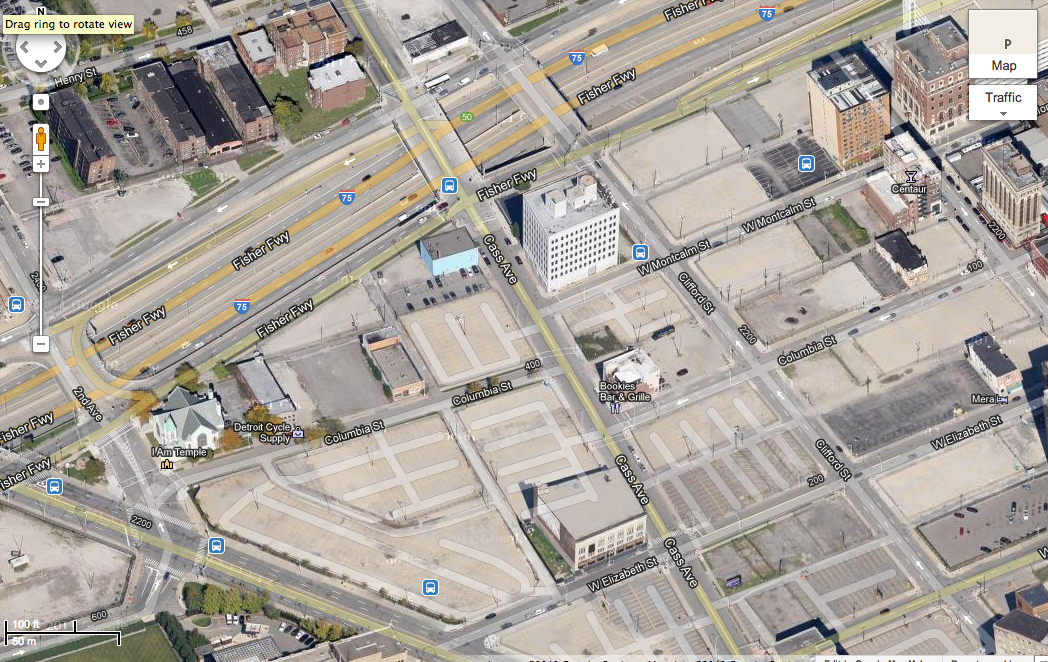

I recently visited the Negro Burial Ground just east of downtown Richmond in Shockoe Valley. My approach to this site was across a VCU parking lot and through a tunnel under Broad St. As you walk through the tunnel, you emerge onto a huge empty field of beautiful grass that was once yet another parking lot in downtown Richmond. In recent years, the asphalt was removed and this area was designated “A Place of Contemplation and Reflection.” I appreciate this area mostly because it’s a complicated place. There aren’t physical buildings that most people would consider “historic,” but what happened on this one piece of ground (the public execution and careless burial of enslaved and free people) is considered enough to make the place significant today. Once a place of fear and violence, it has been restored to the people of Richmond as a place of silence and careful thought. While I think the site itself is certainly worth visiting, what I really care about is a place located just above the actual burial grounds. From this vantage, you can see that less than 50 yards away from this place of contemplation is Interstate 95 in all of its glory. The cars and tractor trailers fly by on this crazy asphalt slingshot that shoots cars straight through the heart of my city. Like all highways, it’s a totally anonymous no man’s land where you don’t walk, you don’t slow down, and you don’t typically notice the historic burial grounds nearby. When you’re on a highway like this, you don’t care much for where you are because you’re more focussed on where you’re going. That’s essentially the nature of movement.

While I think the site itself is certainly worth visiting, what I really care about is a place located just above the actual burial grounds. From this vantage, you can see that less than 50 yards away from this place of contemplation is Interstate 95 in all of its glory. The cars and tractor trailers fly by on this crazy asphalt slingshot that shoots cars straight through the heart of my city. Like all highways, it’s a totally anonymous no man’s land where you don’t walk, you don’t slow down, and you don’t typically notice the historic burial grounds nearby. When you’re on a highway like this, you don’t care much for where you are because you’re more focussed on where you’re going. That’s essentially the nature of movement. There is something so basic and yet remarkable about the time and care that was taken in the planning and development of Hollywood Cemetery. It’s no wonder Richmond’s aristocracy used to picnic on the hills of Hollywood overlooking the James River. They escaped the smoke of the city, tidied up their family plot, and caught a cool breeze on warm summer days. Since the cemetery was first planned, it has been maintained, improved, and today remains a destination in this old American city. A brick walkway was added to create “President’s Circle” where two former US presidents are buried. The cemetery stands, in part, as a testament to the longevity of power and tradition in American society.

There is something so basic and yet remarkable about the time and care that was taken in the planning and development of Hollywood Cemetery. It’s no wonder Richmond’s aristocracy used to picnic on the hills of Hollywood overlooking the James River. They escaped the smoke of the city, tidied up their family plot, and caught a cool breeze on warm summer days. Since the cemetery was first planned, it has been maintained, improved, and today remains a destination in this old American city. A brick walkway was added to create “President’s Circle” where two former US presidents are buried. The cemetery stands, in part, as a testament to the longevity of power and tradition in American society. Another remarkable cemetery in Richmond, one that is not highlighted in Thadani’s epic, is Evergreen Cemetery. I visited Evergreen four days before I visited Hollywood and, as anyone would tell you, the difference is stark. Where one has improved, the other has declined. Where one is prominently placed on the hills overlooking the James, the other is beside a highway in Church Hill. Where one is a testament to power, the Other is a testament to the longevity of systemic stigmatization and shame.

Another remarkable cemetery in Richmond, one that is not highlighted in Thadani’s epic, is Evergreen Cemetery. I visited Evergreen four days before I visited Hollywood and, as anyone would tell you, the difference is stark. Where one has improved, the other has declined. Where one is prominently placed on the hills overlooking the James, the other is beside a highway in Church Hill. Where one is a testament to power, the Other is a testament to the longevity of systemic stigmatization and shame.