*Warning, this post is about race … including white people.

The other day I was driving through Tyler listening to some country music on a local station tryna get in touch with my white roots. As I listened, Eric Church’s incredibly catchy song, “Homeboy,” came on. If you haven’t heard it, the first verse of the song reads,

“You were too bad for a little square town

with your hip-hop hat and your pants on the ground

Heard you cussed out momma, pushed daddy around

You tore off in his car

Here you are runnin’ these dirty old streets

Tattoo on your neck, fake gold on your teeth

Got the hood here snow, but you cant fool me, we both know who you are”

“Hip-hop hat?” “Pants on the ground”? “Fake gold on your teeth?” As I tapped my thumbs on my steering wheel, I wondered to myself, “What is he even talking about?” And the the name of the song is “Homeboy”? Anyone who’s seen Antoine Dodson’s intruder speech (and the requisite autotuned followup) doesn’t have to check Urban Dictionary to know that “homeboy” isn’t really the most white thing you could call someone. So I started thinking about race and how people of different races refer to the other. In other words, how do white people say “stuff Black people do” without really having to say it for fear of sounding racist.

Since I usually write about actual spaces, in honor of Church’s song, I want to get a little more academic and talk about rhetorical spaces. The song constructs two spaces in particular: White (rural) spaces and Black (urban) spaces.

First, I want to talk about the rhetorical space of whiteness as the location from which Church is singing. Basically, Whiteness is the space from which white people often (albeit unknowingly) speak and operate. Whiteness is often compared to a black hole in the sense that you can feel the power of its influence on society, but cannot often determine its characteristics. The blog, “Stuff White People Like” is important regardless of it’s limitations because of its noteworthy purpose: To essentialize Whiteness. When I first saw the blog four years ago it was the first of its kind. Honestly, I don’t think I had even heard the phrase, “White people _____,” in any context. Lots of white people object to the blog (i.e. “I’m not like that” or “That’s just hipsters, not white people!”), but I think that’s partially the point: There are no essential characteristics to a race. It’s also just plain funny.

The objections from white people are interesting because it seems the majority is uncomfortable being “pinned down.” Of course, this is minor in comparison to the experience of African Americans as essentialized minorities. In this world, there are a multitude of examples of Blackness: Stereotypes associated with the black race. These represent the rhetorical space of Blackness. In his song, Church is pretty blunt about his references to Blackness. The song is just full of references such as the ones listed above. As far as I can tell, the song is written about a white guy performing Blackness … basically some guy’s younger brother gets too good for the comfortable, white country lifestyle. Then he starts to cuss, become more physically violent, rebel, become more likely to be thrown in jail, feel entitled, and waste money.

But isn’t that a strange leap? What is it about a tattoo and gold on someone’s teeth that makes them more violent? The reason is this: Blackness, in contrast to Whiteness, is a very defined rhetorical construct.

As a the minority population, black people have often been associated with each other by members of the majority. In other words, for centuries members of the Black Diaspora have been saying, “Hey, I’m not really like that” or “I’ve never seen a black person that actually actually acts like that.” But many white people don’t usually get the chance to feel “called out” for their Whiteness in the same way. If you are white and you’ve been called out for, say, drinking so much milk, you may feel angry thinking about the experience. I usually just laugh. Unlike Blackness, Whiteness is relatively undefined and uninterrogated AND it isn’t historically associated with political oppression. Blackness, in stark contrast, has been constructed over the years with clear political and economic motivations.

The best description I ever heard basically said that Whiteness is an elusive center. It’s relatively undefined and often subtly powerful. In operating from the elusive position of Whiteness, Eric Church seems to be making two statements at the same time. The explicit statement is that there is value in the country life and honoring your family. It’s true: We shouldn’t mock our families or disobey our parents. The implicit statement, however, is that city life is morally inferior and that urban culture or Blackness will lead you down a self-destructive path. There’s a few problems. The first is that rural life is not a white experience. The second is that the WSJ recently reported that city life is in many ways healthier.

As a fan of flat-brim hats, Mike Jordans and doing “The Jerk,” I happen to disagree with the notion that urban culture instills rage or disrespect. In fact, I’ve seen people do some pretty dumb things in Topsiders. Maybe I’ll write an autobiographical counter to Church’s song titled, “Frat boy.” That way, I could engage the ethos of the song which is “Family first” without falling into the pitfalls of race. At this point, I think it’s always important to ask yourself, “What are we trying to say?” As a member of the majority, I think a new kind of thoughtfulness (not merely political correctness) would be appreciated.

Works (loosely) cited: McKerrow, Raymie E. “Critical Rhetoric: Theory and Praxis.” Nakayama, Thomas K. and Robert L. Krizek. “Whiteness: A Strategic Rhetoric.” Also, if you’re interested, here is a link the lyrics to the song I referenced

I believe that the potential of every space is limited by real and imagined barriers. If there are real, perhaps topographical, barriers to building a higher density downtown than I’ll be content to give up this dream. I just don’t think that’s the case. Most barriers I would consider “real” are primarily economic, but as long as people continue to build farther south I’ll contend that they might as well build downtown. To me, it’s the imagined barriers that I can’t stand. If it’s a zoning issue, some regulation, or a city of small dreams then I won’t be satisfied. Cities do not become great with small dreams. Cities become great when people do bold things that the mainstream calls crazy. Take, for instance, the Seattle Public Library (pictured). This building is a strikingly beautiful and completely functional structure that could theoretically be built anywhere on any square piece of land. In Seattle, they love it. Could we love this library? I should add, there are people in Tyler doing great work to revitalize our downtown, but I’m just not sure whether the public will appreciate it.

I believe that the potential of every space is limited by real and imagined barriers. If there are real, perhaps topographical, barriers to building a higher density downtown than I’ll be content to give up this dream. I just don’t think that’s the case. Most barriers I would consider “real” are primarily economic, but as long as people continue to build farther south I’ll contend that they might as well build downtown. To me, it’s the imagined barriers that I can’t stand. If it’s a zoning issue, some regulation, or a city of small dreams then I won’t be satisfied. Cities do not become great with small dreams. Cities become great when people do bold things that the mainstream calls crazy. Take, for instance, the Seattle Public Library (pictured). This building is a strikingly beautiful and completely functional structure that could theoretically be built anywhere on any square piece of land. In Seattle, they love it. Could we love this library? I should add, there are people in Tyler doing great work to revitalize our downtown, but I’m just not sure whether the public will appreciate it. Another possible impediment to Tylerites embracing urban life is a lack of

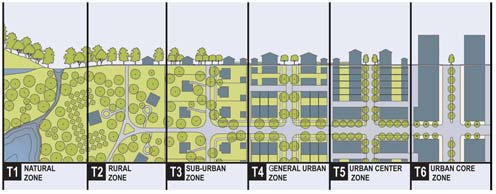

Another possible impediment to Tylerites embracing urban life is a lack of  Look at the arial photo of Tyler to the left. These nine city blocks should not look like everywhere else in the city because if they do then they will be no longer be significant. Downtowns are places where you can live to not only experience the diversity of other people’s lives, but most importantly you can personally add to the diversity of self expression, culture, perspective, race, ethnicity, etc. When we begin to add to this multi-cultural society and invest in the community we become a part of organizations and we learn what it means to be citizens instead of consumers. I don’t want us to “consume” downtown as entertainment the same way we sometimes consume church, media and everything else. Rather, we must commit to downtown as an idea and be unified on our goal at the outset. This idea is that, in many ways, downtown is what we look to as the zenith of our city’s development. I believe there is an inherent value to dense urban downtowns as the site of culture creation, political debate and financial stability. Our downtown is a vital element of the future of our city as the capitol of East Texas. We need a viable downtown option, but we have to want it. And we have to know what it is.

Look at the arial photo of Tyler to the left. These nine city blocks should not look like everywhere else in the city because if they do then they will be no longer be significant. Downtowns are places where you can live to not only experience the diversity of other people’s lives, but most importantly you can personally add to the diversity of self expression, culture, perspective, race, ethnicity, etc. When we begin to add to this multi-cultural society and invest in the community we become a part of organizations and we learn what it means to be citizens instead of consumers. I don’t want us to “consume” downtown as entertainment the same way we sometimes consume church, media and everything else. Rather, we must commit to downtown as an idea and be unified on our goal at the outset. This idea is that, in many ways, downtown is what we look to as the zenith of our city’s development. I believe there is an inherent value to dense urban downtowns as the site of culture creation, political debate and financial stability. Our downtown is a vital element of the future of our city as the capitol of East Texas. We need a viable downtown option, but we have to want it. And we have to know what it is.