I recently read an article about three colleges in Virginia that are showing signs of financial trouble. Apparently the “enrollment cliff” is set to begin next year and all institutions of higher education in the US will be affected by a shrinking domestic applicant pool. Some Virginia schools like Sweet Briar College have threatened closure and others, including HBCUs such as St. Paul’s College, have ceased operations.

The article reminded me of an idea I’ve been mulling over for at least a decade: that colleges and universities could somehow incorporate retirement communities into their campus life. While the enrollment cliff approaches, the Silver Wave (or Tsunami) is already over a decade in and will increase in the years to come. By 2030, there will be nearly a billion people over the age of 65 worldwide – by that same year, older Americans will make up 21 percent of the population.

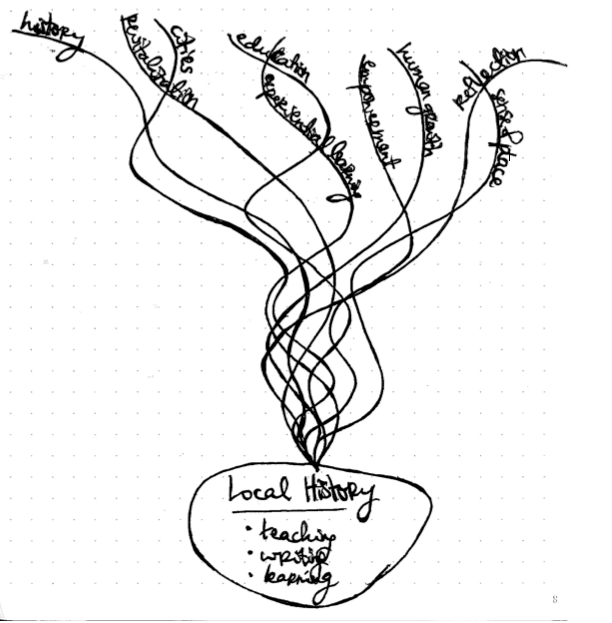

This post is more of a brain dump, but I do hope to do more research, look into case studies, and hopefully plan some field trips to consider the different aspects of an intergenerational college campus. The following are some potential positive outcomes I’ve considered over the years.

- There are obviously incredible financial benefits to building retirement communities. Baby Boomers will need places to live and they have the wealth and benefits to afford high-quality options.

- Retirees will have the benefit of living in a vibrant place full of enrichment opportunities including

- Cultural events

- Continuing education

- Sports

- Dining options

- Wellness facilities

- Retirees could elect to be buried on campus in a cemetery or columbarium, a beautiful location where they could be remembered and visited

- Retirees could serve in a number of capacities on campus

- Formal and informal boards for oversight

- Advisers for student organizations

- Mentors for students

- Serve in the career center based on their professional experiences

- Volunteer in the community

- Students from many different disciplines could benefit from having older neighbors

- Psychology students would benefit from their research being more diverse in terms of age

- History students could practice interviews and gathering personal narratives and incorporate first hand sources, artifacts, and perspectives into their research

- Students in the medical and allied health professions would benefit from practical experience volunteering with community members that have health needs

- Business students could do market research to understand the needs and desires of a growing consumer population

- Philosophy students could consider the meaning of life with people who are near the end of it

- Biology students could study their bodies after death to learn about degenerative diseases

- Colleges and universities could bring a new and innovative option to the market

- With a commitment to diversity and inclusion these communities could be safe spaces for individuals at the end of life

- With their beautiful and walkable campuses, colleges would be the ideal setting for active, enriching retirement life

- With their endowments, colleges could invest in all sorts of solutions to improve quality of life for residents in ways that aren’t available to existing retirement communities

- There is enough demand for retirement communities and the associated labor that institutions could even transition into “work college” models like Berea, Warren Wilson, and others to reduce or remove the need for tuition

While writing this post I learned for the first time that there is a project underway to “reimagine” the empty campus of St. Paul’s College which seems exciting. A non-profit, SPC4LIFE, is organizing to purchase and reopen the college in some capacity and their mission, “creating an equitable, family-based academic environment,” seems to align beautifully with a multi-generational campus design.

Ever since St. Paul’s College closed I’ve been imagining it as the perfect location to try something like this. It’s only an hour outside Richmond and only a little farther from Durham which seems like a good location – inexpensive and accessible. One of my favorite aspects of the college campus is how integrated it is with the town of Lawrenceville, a historic and walkable area with amenities for residents to enjoy. A lot of the town appears to have been demolished, but there might still be enough of a historic core to inspire rezoning if needed and future dense, mixed-use developments.

I am definitely going to follow along with their progress and I am going to plan a visit some day to see the town, the campus, and imagine what it could all look like with some vision and a lot of work.