Over the course of this blog, I will often write about space and place. This post is my attempt to clarify these two terms because they are ultimately the two underlying concepts of each post. While I draw from theorists such as Foucault and Said, I have eventually developed my own way of thinking about life through these lenses.

The two words, in my opinion, are completely distinct from each other. Space is the void. Space is the physical, tangible built environment in which we live. Space is buildings, roads, houses, parks, landscapes. Space is the void. Place is the life. Place is the culture that is created within a space. Place is what makes a house a home. Place is created when people congregate, communicate, experience each other. Place is a conversation in a coffee shop or a fight outside your house. Place is the life.

These concepts of space and place are often used in casual conversation. Consider the phrase, “I’m just not in the right place to make that sort of decision.” This common refusal is usually considered metaphorical as in an emotional state or a level of maturity. But, what if the person is thinking of actual places where they have experienced significant emotional attachment to other people and are not prepared to enter those places again. Or what if the person has a close tie to a person that lives in another space and they aren’t willing to leave? These are the memory places that are informing the person as they make the decision to move forward or remain.

We all know spaces such as these where we have invested time, emotion and energy to create place with another. We have struggled to be accepted into the group of people that make up these places or we have revelled in our influence over them. It is in these places of human interaction that we struggled through love, lust, pleasure, loss, enlightenment, rejection and friendship to eventually reach some sort of comfort. No matter how frightening these places are, what is more frightening is the thought of leaving them. In these places we become ourselves, we find our identities and we are unsure how that will change when we leave.

Pardon the long quote below … I think it helps me to understand what I am saying:

In his book Repairing the American Metropolis, Douglas Kelbaugh writes, “As others have pointed out, spatial boundaries demarcate the beginning of a place as much as the ending of a place and its power. Boundless architectural and urban space has less nearness, less presence. Limits are what differentiate place from raw space, whether they separate sacred from profane space or one secular space from another.”

The “spatial boundaries” which demarcate place are the physical boundaries which affect the human interaction within that space. These are often used to enhance the experience of existing in a certain space, but they cannot alone create space. Without humans a space is meaningless. In the same way, it is humans that give space meaning regardless of the intent of the design of the place. All throughout history there have theories about cities which attempt to create the perfect society with the perfect spaces. Le Corbusier’s La Ville radieuse is a common example of this delusional habit. But we have learned time and time again that you can’t solve problems with new space: Housing projects and suburbs are two great examples. They were both dreams for a better life, but both inhabit miserable and satisfied people alike.

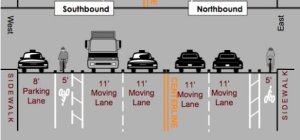

It is places that people crave. To me, it is not easy to create place with another. To be honest, many people don’t create place because they don’t linger in a space for long enough. Think about a highway. It is the space par excellence. There is only movement and stigma on the highway — no life, no place. It is one, uniform, vacuous space. And how many of us spend hours each day in these spaces? In contrast, a place can be anywhere. I remember four friends and I had an impromptu gathering in a chapel recently that created the most beautiful place of fellowship. I recently wrote that graduation was an instantly nostalgic place where people gathered from all over the world. It was not “The University of Richmond” that weekend, but instead it was transformed by the presence of a multitude of people that had gathered for the same purpose.

I don’t want to limit myself with these terms, but I sincerely believe they illuminate my perspective on the city and society. I will likely link back to this post many times in the future for reference … they’re my words, but the concepts belong to many people. I’m excited to see how far I can take them.

*Repairing the American Metropolis: Common Place Revisited. Douglas S. Kelbaugh