For the last week or so I’ve been thinking about the Celtic holiday of Samhain. I don’t know much about the Celtic holidays, but I read a book once about a home called Bealtine Cottage and at the very least the idea of Bealtine planted a seed in my mind.

After some deep dives, I’ve learned that Samhain is essentially the “pagan” holiday that Catholics co-opted when they created All Hallows Eve (and All Souls, etc.). In a further twist of colonialism, it is also basically the origin of Dia de los Muertos – a holiday some see as a Catholic invention/amalgamation of existing rituals and beliefs.

Anyways, a witch on Instagram made a video saying that tonight is actually the best time to set resolutions and to plan for the work ahead. This night marks the end of the Celtic year and the beginning of the “dark half” of the year. This is a time when we are inside more, when gardens and farms have begun to rest. We often use this time to focus inward and draw close to friends, family, and partners.

With all this energy in the air, I decided it was time to take some small steps of preparation. With the help of our kids, we cleaned out several bags of toys and started to organize their play area. That felt like a nice small win. I am thinking about the fact that I’ll be inside more soon and feeling a desire to organize and repair more in general – there are so many projects that weigh me down more than I even realize.

I also decided to start the new Life Designer workbook from Intelligent Change. I bought it before the Samhain connection, but soon realized that it would be perfect for this (new) new year.

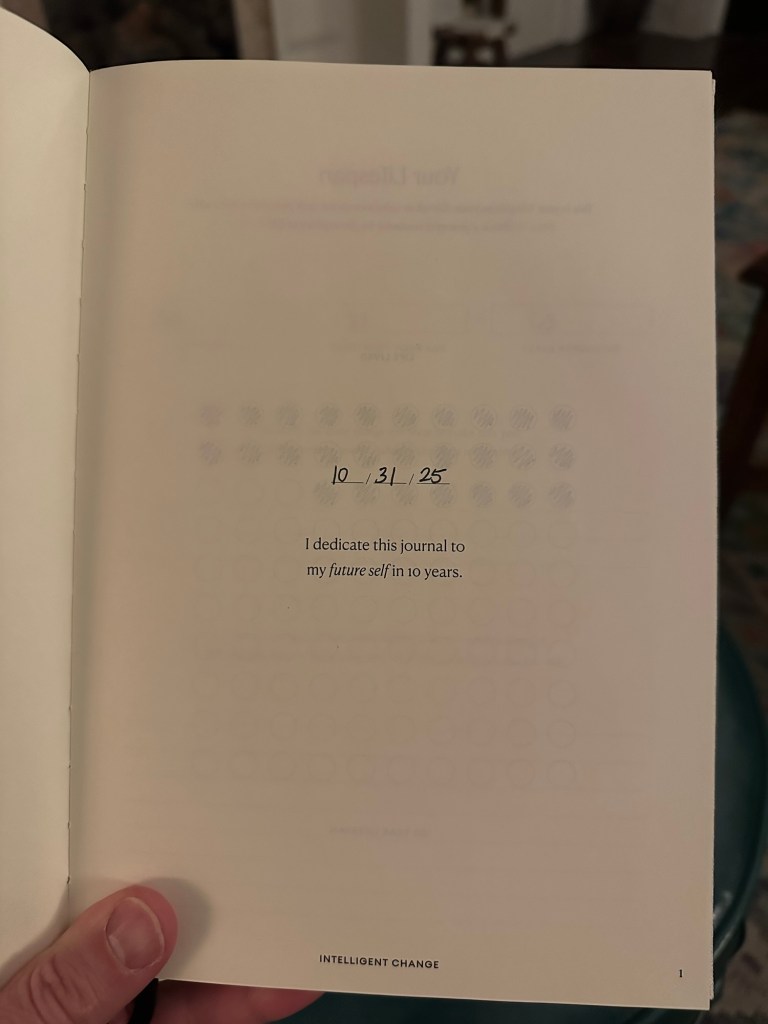

At it’s core, it’s a workbook to plan the next ten years of my life. On October 31, 2035, I’ll be 47 years old. I actually started crying just typing that sentence.

Oh, I also cried when I filled in this dedication page:

I really do not want to get older – I don’t know how else to say it. On the other hand, there have been so many days in my adult life that I’ve just wanted to be over so that I can sleep again.

I know that I have to fix my days before I can fix my years. And since I can’t avoid age, I can’t avoid work, I can’t avoid relationships, hopes, disappointments, responsibilities, etc., I know that it’s time to start thinking about what I want to build on the years I’ve lived so far. Because “the next ten years” are already here.

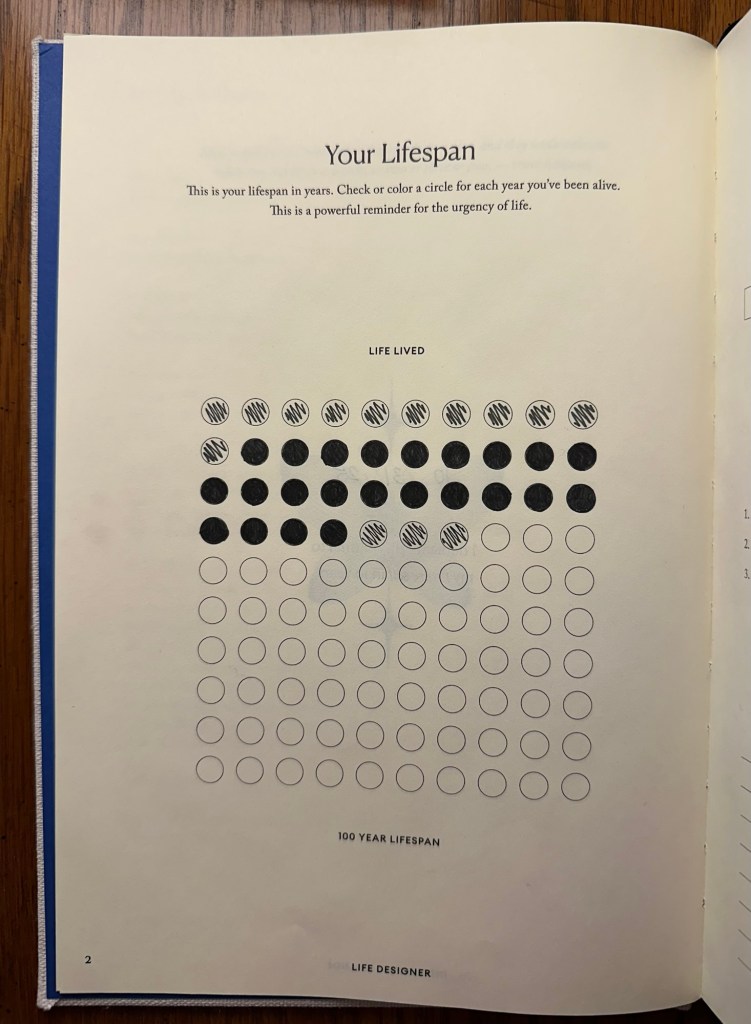

With my fear of getting older, it was encouraging to fill out this chart of the years that I’ve lived so far and see how many I presumably have left.

Even if I live to be 70 or 80 I still have a lot of life ahead of me. The first time I posted this page I did it wrong so this is a new photo. Also, I decided to black out the years that I was in the closet. I cried for a moment when it sunk in that I’ve only lived around 15 years of life not in the closet. Hiding took such a toll on me that I need to label those years differently. Also, being in the closet delays adolescence (like what a 15 year-old would be experiencing) so the past three years have looked very different than they would for someone who is not going through that.

I’ve only just started this workbook, and, based on the witch’s advice, I would like to finish it between now and the Winter Solstice. (update – I’m still working through it as of 1/20/26, but I’ll finish it when the time is right)

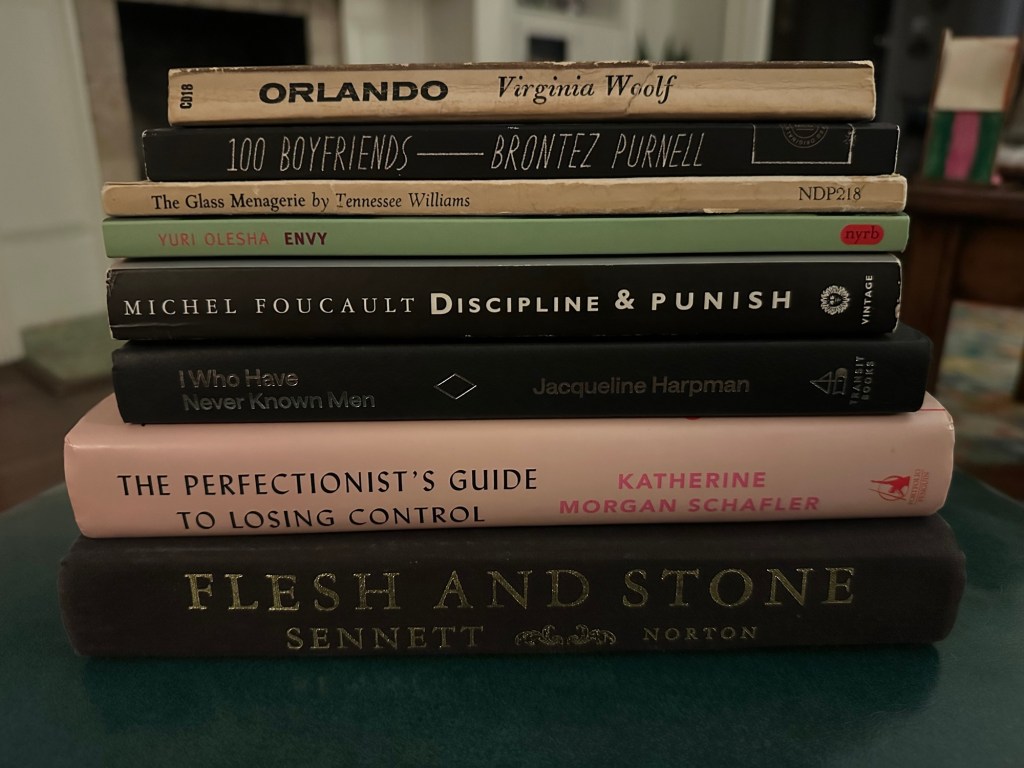

With the seasonal shift toward intentions, I also thought about books I might like to read over the next 12 months. I’ve pulled together a stack that I’m pretty excited about and replaced the one under my side table that has been sitting there for months (years?), mostly unappreciated. This new stack was chosen more carefully and I’d love to actually see the stack tick down as I read each one and the shelf empty by the next Samhain, 2026.

I started the Foucault and Sennett books around 2008 and 2011, respectively. I’ve only read the first chapter or so of each, but they have both been so influential to how I think about things that I’ve decided I’d like to finally finish them. Along with those two books, Orlando, 100 Boyfriends, and The Glass Menagerie continue to round out my gay literature cannon. I Who Have Never Known Men and Envy (a personal problem, unfortunately) are two foreign language books I’m looking forward to. Finally, The Perfectionist’s Guide to Losing Control, a book I started during a hard time last year and have decided to pick back up during a new season of loss.

So much of this post may seem like I am trying to control my life, but I really do want to lose control more than anything. I want to let go of legalism, perfectionism, and self-criticism, especially. I am not going to feel like a failure if I don’t read all these books or achieve the life I envision exactly. I just know that there are some things in my life that almost never feel like work (even when they are work). I desire/intend to do much more of the work, to spend time with the people, and to inhabit the places that give me that kind of energy over the next 40 seasons of change.