When I finally started to come out of the closet, one of the ways that I processed my story was by reading through old journal entries.

So much has changed over the years and looking back has helped me connect with my younger self as well as understand why and how I managed to stay in the closet for so long. One particular aspect that feels important is that I had a long-term relationship with a “Christian counselor.”

The person I saw is a licensed therapist, but we always called what he did “Christian counseling.” And it did feel different from the therapy that I’ve experienced more recently. This post is not to drag an individual, but I am definitely critical of the idea of Christian counseling overall.

My main critique is simply that much of the “Christian” aspect is not based on research or best practices. For instance, here are some ways that Christian counseling is different from therapy in my experience:

- My counselor prayed for me at the end of every session and asked that God would support me in my struggles. Prayer is seen as an encouragement, but in my experience it was often a way for me to give up control of my life to God. This prayer at the end of the session may have had the effect of undoing some of the progress I had made to become more self-determined.

- They very frequently related my problems to “the fall” which basically means that my problems were a result of my “sin nature.” The emphasis on sin and “the fall” may have reinforced the feeling that my problems in life were intractable. In other words, I was not empowered to solve them.

- My Christian counselor seemed a little too comfortable with my suffering. They did not really seem to think of it as something that needed to be fixed. Some things could be changed, but in general, Christianity and Christian counseling taught me that suffering was good for me, that it is God’s way of testing our character, and, bizarrely, that it means we are doing the right thing because God is teaching us something through the suffering.

- I don’t remember them affirming my sexuality in a meaningful way, preferring to make general statements that were not untrue, but also not very helpful like, “It’s always going to be a part of you.”

- One phrase they repeated many times was that “every man feels like they aren’t enough and every woman feels like they’re too much.” This was mentioned in individual therapy as well as in couples therapy. The idea apparently comes from God’s curse of Adam and Eve in Genesis which I might try to unpack in another post. For now, I’ll just say that I don’t typically find generalizations around gender to be helpful and that these kinds of religions aphorisms often end what could have otherwise been a productive inquiry.

When I first decided to start seeing a Christian counselor (with much encouragement), I was so scared to talk about my personal life that it certainly came as a relief to find someone I could trust. I needed a lot of help and in many ways found the support that I was looking for. It was even somewhat affirming to hear things like the idea that my sexual attraction would always be a part of me. I was raised to think of sexuality as something that could change so in this sense, I didn’t technically receive conversion therapy. I feel like what I received was more similar to the hypnosis in “Get Out.”

If you haven’t seen it, the general premise of the movie is that old, wealthy white people pay to have their brains transplanted into younger, Black bodies so that they can be active and young again. Before the transplant can happen, however, the victim had to be hypnotized so that their consciousness is sunken to a deep part of the brain stem. With the completion of the brain transplant, the consciousness of the older person has essentially replaced that of the younger person – they think, talk, operate the body, etc. But the hypnotized consciousness is never fully removed. It stays in the brain stem unless it’s triggered by a flashing light like that of a camera and the trapped person escapes back into their body (very dramatically) until they are hypnotized again into the subconscious.

In discussing drafts of this blog post with friends (both gay and straight) I received encouragement that the metaphor was helpful for understanding their experience in Christianity. Many aspects of our lives can be suppressed and there are triggers/moments when we wake up to realize we aren’t really the ones living them. One time in grad school a classmate told me that when he first met me he thought that I was gay. I was shocked and I completely froze in the middle of our conversation – I have no idea what I even said in response. Years later my therapist (not a Christian counselor) asked me if I thought I had disassociated. After some thought I told him that it was actually the opposite – I had been disassociated and his question has brought me back into myself. I was just too afraid of the world to say anything.

I have thought about the sunken place and identified with the idea of it for many years. One thing I want to add is that when I was in Christianity there was a part of me that wanted to stay in the sunken place – out of fear, self-preservation, rewards in heaven, etc. In that sense, the Christian counselor is sort of a co-conspirator in the sunken place. They know that the liberation queer Christians seek in counseling is constrained by the rules of their shared faith so they help their clients find significance and meaning within the sunken place rather than providing them with the tools they need to get out. I do believe that this is why I felt safe with a Christian counselor, but also why I eventually grew out of the limited support they were able to provide.

Even though my counselor and I agreed my sexuality would always be with me, the agreement was that it shouldn’t need to “dictate” my decisions or be a significant part of my life. In our conversations, my sexuality was more of a “thorn in the flesh” kind of situation where it would be something that God would use to teach and humble me. My counselor encouraged me to talk about it, but not in the sense of coming out. It could just “be there,” under the surface, suffering silently, for my entire life. The Christian, I was told, is divorced from their sexuality.

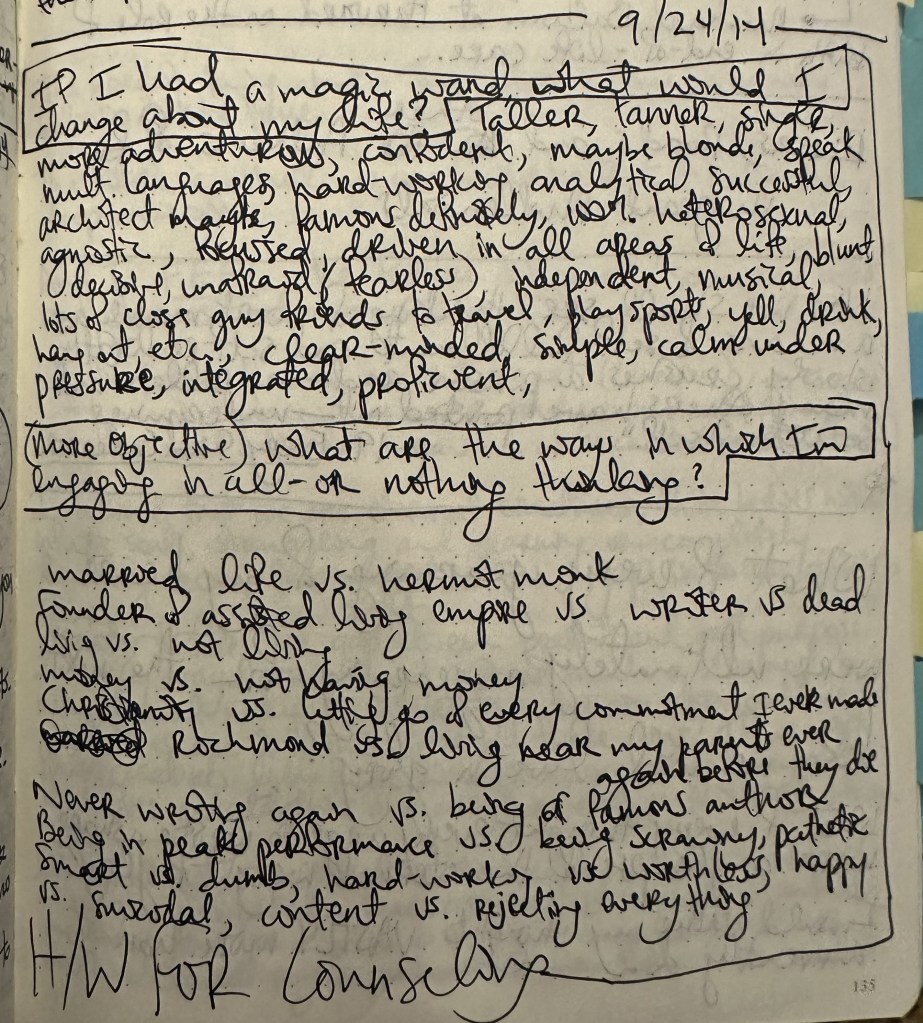

When I was 26 years old I wrote the reflection below as homework for counseling. (For a link to a transcript of this handwriting, click here.)

I was very clearly holding on to a lot of internalized homophobia, but I do not remember my Christian counselor seeing this as a problem or helping me to recognize and let go of it. “If I had a magic wand,” I wrote, I would have made myself “100% heterosexual.” I was struggling with body-image issues, self-criticism, and a general lack of confidence. I wrote that I wanted lots of close guy friends, but had to couch it in masculine terms like “play sports, yell, drink” rather than just say I wanted to be around men because I wanted to. I couldn’t say I wanted to dance with them, kiss them, laugh with them, go to the beach or Broadway, etc.

Looking back at this entry I am reminded that I talked and wrote about my own death a lot in those years. I felt trapped by my life. Rather than encourage me to come out of the closet and let go of my fears, I was encouraged to pray about my sadness, share my story with other Christians, and keep my life moving forward trusting that God would figure it out for me along the way.

Instead, I wish I had been encouraged to take risks and actually listen to my needs in a way that might have helped me find a supportive community, my voice, or a life that I desired. I am grateful for the safety of my counseling experience. I also can’t help but feel like during those years I was drowning and every time I came up for air my Christian counselor gently pushed me back under water.

I have at times considered my experience in religion as a kind of brainwashing, but as I’ve reflected more (and read some critiques of the idea of brainwashing) I’ve become more specific about the ways I was shaped by religion as I experienced it. I believe that my religious life resulted in a decreased self-esteem, inability to listen to my intrinsic desires, and a fear of the outside world that left me overly cautious in my decision-making, isolated from my community, and overwhelmed by the pressure of evangelism.

Maybe a more accurate and contemporary term would be that I was groomed. I was groomed to look for someone to take care of me, handle all my problems, and essentially to live my life on my behalf. I was groomed to give up agency, blame myself for my problems, and wallow in my sadness rather than solve my problems and move on.

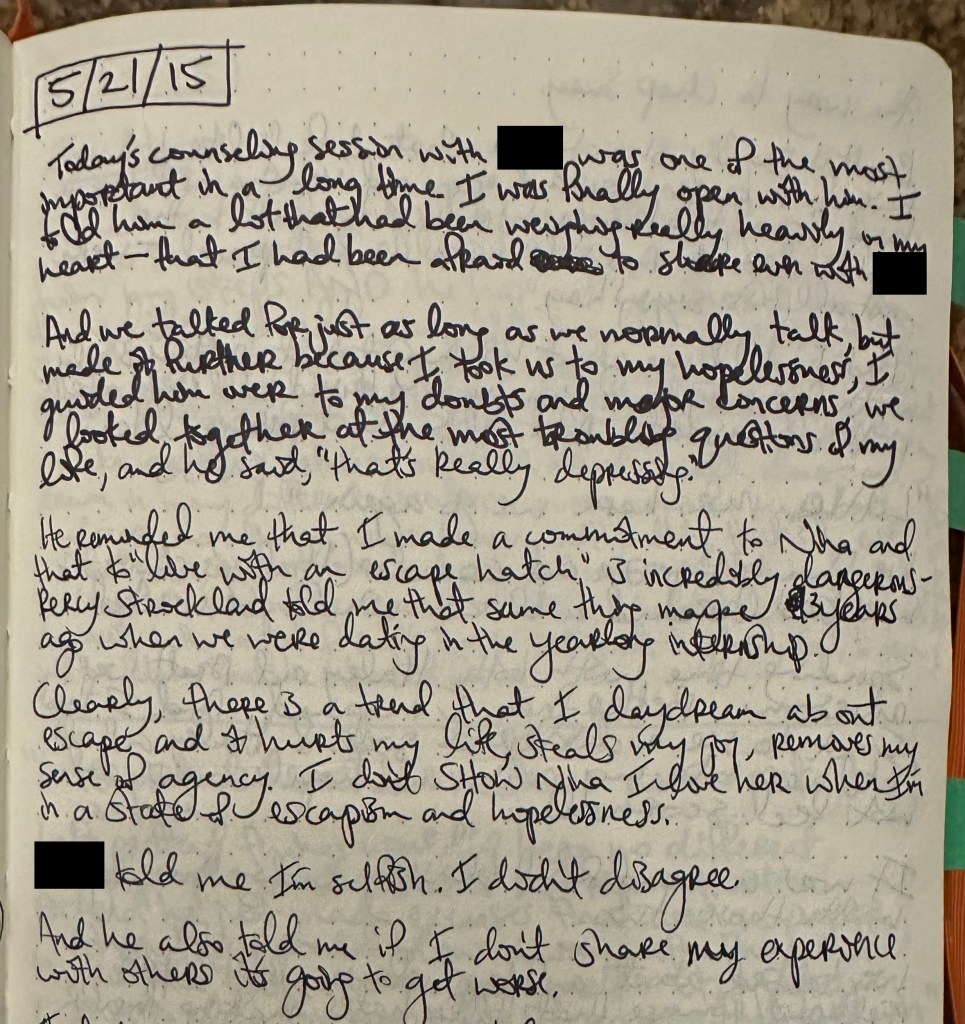

Below is a journal entry where I reflected on a time when I shared more with my counselor about my sexuality (with their name covered) and “felt a peace” about my life despite my reservations. (For a link to a transcript of this handwriting, click here.)

Looking back on this journal entry after coming out I wrote “WHAT THE FUCK” on a Post-it note and stuck it to the top of the page. It’s painful to remember how repressed I was and sad to see how much it affected my quality of life. These journal entries seem like moments when I almost made progress then, with encouragement from my counselor, recommitted to the status quo. I wanted to change my life, but I was too afraid to do it. Instead of help me push through the fear, I was told that I was selfish and reminded that promises are binding for life.

It’s weird to think that sadness, loneliness, and hopelessness could be interpreted as selfishness, but within the context of Christianity it does make sense. Your life exists for the glory of God and longing for anything other than the life you’ve been given is placing your own self-interest above God’s plans. This perspective fit into my worldview at the time and I didn’t question it.

I also think that I accepted what they told me out of self-interest and self-preservation. I was overwhelmed by the amount of change that might occur in my life if I actually came out. I thought the whole world would fall apart. I thought I would be an embarrassment to my family, and I was probably even afraid of losing my marriage. My spouse and I had become huge sources of support for each other over the years and our relationship felt too important to lose.

In reflecting on this journal entry, I wish the person counseling me had told me some of the lessons I have learned since we ended our time together. I wish they had told me that clear is kind, that love cannot exist without honesty, and that my partner and I were strong enough for the truth that I was holding in my heart. I wish he had told me that I needed to let go of the responsibilities and obligations I felt to everyone but myself.

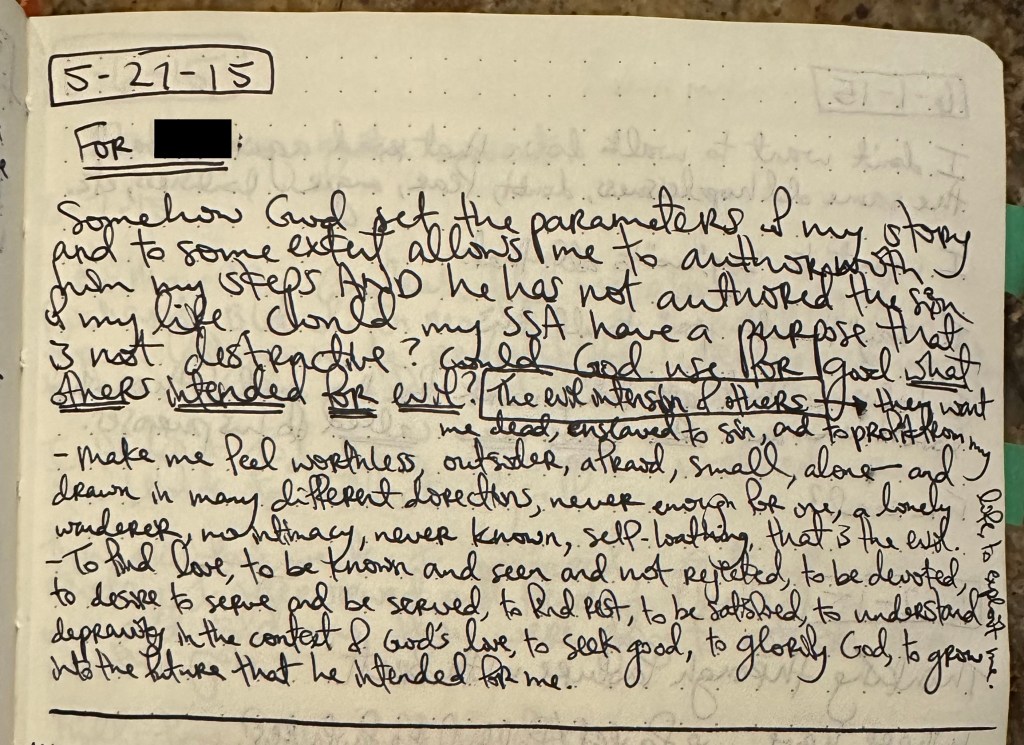

The next journal entry is a reflection I wrote in advance of counseling or as homework after a counseling session. (For a link to a transcript of this handwriting, click here.)

In this reflection find myself, once again, giving control of my life to God and hoping for the best. God “set the parameters of my life” and I was trying to accept that and believe that these parameters were placed in my best interest.

Part of what made God’s plan good, I thought, was that I was being protected from the LGBT community. I had been led to believe that the LGBT community was dangerous and essentially evil. I write, “they want me dead, enslaved to sin, and to profit from my life, to exploit me.” I had been taught to have so much irrational fear towards the very people who might have wanted the best for me. As I have come out of the closet I have not felt worthless, like an outsider, afraid, small, or alone. I have felt the exact opposite. I have felt understood, safe, and affirmed. All this fear of the outside world feels a little cultish actually. I was isolated from my community, too afraid to explore and find out whether happiness could exist outside the world that I had known.

One thing I’m still thinking about after reading this journal entry is how I believed that I could only feel “known and seen” within the context of Christianity while I was very fervently (consciously or unconsciously) holding back a huge part of my life. How could I believe that coming out of the closet and joining the LGBT community would make me feel “never known” and “self-loathing” when the opposite is so obviously the case?

It’s a bit of a mindfuck, but after some reflection, I think I have finally wrapped my head around it. I think Christianity successfully convinced me that my sexuality was not a part of me, and that actually much of “me” was not a part of me. Instead, my true self, the one that mattered, was the ideal self that God was theoretically transforming me into.

So I could truly believe that I wasn’t being dishonest or holding anything back from anyone while staying in the closet because I was sharing with the world what was true about me – what God had done in my life and the plans God had for my life. That was the version of me that I wanted to be “known and seen” and that was the only version of me that deserved to be known and seen. That was the version I could plan a future for. The rest of me was essentially disregarded as sin or evil. I was taught to repent of all of the bad parts of me and run away from them, to take those thoughts “captive,” and literally for those parts of me to die. In this way, much of me, not just my sexuality, was hypnotized into the sunken place.

If those parts of me including my sexuality had been killed/taken captive/left behind, then I wasn’t really hiding anything because it wasn’t there anymore. And if it “came up” every once in a while I just had to pray about it and ask that it would go away again so I could go back to living my true life as God intended – the only life that I wanted others to see and know. My dishonesty was completely justified, sanctioned, and encouraged by the Christian faith, at least in my personal experience of it.

It has been a painful, healing process for me to piece together these three artifacts from my past. For many years my journal was a safe space for me – one of the only safe spaces in the world. It feels very liberating to finally let these words out into the world as they always should have been.